Research Background

In delving into the realm of urban public spaces, let us commence our exploration from the annals of public space history. Indeed, the term “city,” employed to delineate vast human settlements geographically, inherently encompasses a pivotal variant of public space—the market, a locus dedicated to commercial transactions.

From the Spring and Autumn Period to the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the evolution of ancient Chinese cities traversed a phase dominated by enclosed markets, epitomized notably by the East and West Markets of the Tang Dynasty, embodying traditional agrarian-commercial policies and control over the mercantile class. Subsequent to the mid-Northern Song Dynasty, enclosed markets gradually yielded to street markets, heralding an era of openness and vibrancy in urban life, signifying the emergence of a civic stratum in ancient Chinese urban societies. Commercial venues evolved into the central hub and paramount public spaces of civic life, a characteristic still resonant in contemporary Chinese urban landscapes.

Furthermore, spaces for resident interaction and communication proliferated. Temple fairs, originating from temples, evolved into distinctive cultural events during the Song Dynasty, continuing to furnish avenues of entertainment for citizens to this day. The guildhalls of the Ming and Qing periods, structured akin to familial compounds, transcended regional confines to serve as novel public spaces. In the realm of cultural and recreational pursuits, open streets and alleys provided new venues for folk artistic performances, giving rise to established venues for performances such as the “wazi.” Gardens, functioning as public spaces, proffered scenic and tranquil settings for leisurely strolls and recreational activities. Notably distinct from Western cities where squares hold prominence, the core of ancient Chinese cities lay in palaces or governmental offices, spaces seldom accessible to the public. In summation, ancient urban public spaces manifested characteristics of dispersed derivation, commerce and entertainment centrality, introverted small-scale nature, and secular essence.

While modern-day assembly activities in China primarily unfold on urban streets, public spaces conducive to civic political life remained scarce in cities. However, post-1949, this landscape underwent a profound transformation. With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing as the capital saw the prioritization of political public space development. Following renovation and expansion, Tiananmen Square emerged as a historically significant urban plaza, serving not only as a public space for Beijing but also as a national public arena.

Presently, across Chinese urban landscapes spanning from metropolises to small townships, a plethora of public spaces like commercial streets, urban squares, parking lots, green parks, and sports fields continue to burgeon. This metamorphosis mirrors the rapid economic growth and accelerated urbanization in China. The rise in per capita disposable income has elevated the living standards of the majority of urban residents, transitioning from mere sustenance to affluence, from mere sustenance to leisure, with every urban square in China showcasing this progress. For instance, square dancing has become the quintessential activity emblematic of contemporary Chinese urban public spaces, vividly showcasing the kaleidoscope of activities within these spaces. The diverse activities within urban public spaces are shaping the core values of the nation, displaying its prosperity, multiculturalism, and contemporary visage. As potent instruments for showcasing national image and culture, urban public spaces hold immense research value.

Literature Review

Study of Urban Public Spaces

From Social Space to Urban Public Space

Throughout the past century since the rise of sociology in the 19th century, sociologists’ conceptualization of space has been continuous. The notion of space, through profound discussions by French social thinkers, gradually extended towards the more abstract category of “social space.” Whether it be Bourdieu’s “field” or Lefebvre’s “production of space,” they all argue that social space, in contrast to other concepts such as social structure, social systems, and social networks, focuses on the actors, locations, and their relationships. It emphasizes the structural nature of social space, influenced by Marxist theory.

The theories of social space by Simmel, the first generation of the Chicago School, and Goffman present different understandings of social space, viewing it as the setting for social interactions and emphasizing the influence of social structure on individual behavior. Simmel posits that social space possesses cohesion, conscious boundaries, and underscores internal relationships within space. In his theory, social distance entails not only physical proximity but also emotional dimensions of interpersonal relationships. Goffman, through “Relations in Public,” further investigates how individuals organize the spaces around them.

Urban public space, as a specific form of social space, emerged in the 1960s in the United States during a period of acute urban issues, gradually gaining acceptance through the advocacy for citizen rights maintenance by planners like Jane Jacobs. By the 1970s, the concept of urban “public space” took shape, becoming a platform for urban issues and the built environment’s exploration of social relations in cities. Defined in Li Dehua’s “Principles of Urban Planning,” urban public space is described as outdoor spaces for the daily and social use of urban residents, encompassing streets, squares, outdoor spaces in residential areas, parks, sports facilities, and more. Moreover, the book suggests that the broad concept of urban public space can extend to spaces for public facilities, such as city centers, commercial areas, and urban green spaces. This definition of public space is essentially synonymous with outdoor spaces.

Whether in the production-oriented spatial sociology or the situational spatial sociology, the focus has often been on studying space directly, with little attention given to the activities of individuals within that space. Yingli Cheng et al. (2019) propose a preliminary concept of “use-experience” spatial sociology, reinterpreting the production and situational aspects of space from the perspective of space participants. This proposition offers a new approach to studying “individuals.” Urban public space similarly follows this research direction, with a focus on the ontology, attributes, characteristics, and determinations of public space, while often neglecting the study of residents who use urban public spaces. In recent years, scholars have delved into the perception and supply mechanisms of residents, with Liu Ru et al. (2022) considering residents’ perceptions as a factor in measuring spatial justice, exploring solutions to optimize spatial justice starting from residents’ attitudes, thus filling the gap of micro-quantitative research in spatial studies. Sang Jin et al. (2023) propose that in addition to the government’s direct supply of public spaces, a “bottom-up” supply mechanism involving stages of “value discovery—individual action—government response—institutional evolution” is needed. In this mechanism, the public is studied as a supply entity, serving as a supplement to the study of residents in urban public spaces.

Public Space and Art

The concept of public art originated in the United States in the 1960s and was first introduced in China in the 1990s. Early understandings of public art primarily viewed it from an artistic perspective, considering it as a form of art used for beautifying the environment and decorating spaces.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, research on public art in China has undergone a significant “social turn.” Yang Wenhui (2004) focuses on the development of modern Chinese cities and the evolutionary history of public space art, emphasizing the organic integration of public space with the natural environment. Zhou Chenglu (2005), from a sociological perspective, interprets the public nature of art, noting that the power dynamics within “public space” are of great public concern. Zou Feng (2005) argues that the development of the Chinese economy and society has led public art to shift from defining traditional elite forms that represent national values towards a direction that caters to the aesthetic preferences of the public, maintaining a strong social aspect throughout its development.

Sun Zhenhua (2009) further advances the core concepts of public art, including the pursuit of publicness, the transformation of sociology, and the specificity of regions and places. He believes that the planning of public space must be supported by social research to fully understand the impact of art on the public. This “social turn” reflects the economic and social development in China, integrating the public more deeply into the study of public spaces.

Public Spaces and Communication

The discussion on urban image and mass communication has a long history. However, the study of communication in urban public spaces has gradually emerged alongside the “social turn” of public art in China, displaying a certain synchronicity. Therefore, the research on communication in urban public spaces also considers visual expression as a significant subject of study. Zhao Junxiang (2015) explored the design of museum public spaces within the context of visual communication, proposing a unified perspective on visual communication, visual aesthetics, and visual order. Lin Yuancheng et al. (2021) found through empirical research that promotional outdoor advertisements create emotional spaces through visual representation, enriching spatial governance.

With the development of intelligent visual technology and digital communication technology, research on communication in urban public spaces has shifted towards the mediatization of these spaces. Su Zhuang (2012) and Chen Lin (2016) conducted studies on public screens and museums, highlighting the role of public spaces as mediums for information dissemination and cultural display, which hold significant importance in the construction and identification of cities. Yan Ya (2017) proposed that “urban spaces are constructed as ‘scenes’ through their connection with the body, where the body is observed within the ‘scene’.” The youth express a desire to engage with urban spaces, deconstructing traditional “center-periphery” urban structures within mediatized urban spaces. Pan Ji (2017) suggested, from a geographical media perspective, that media technologies link spatial elements and cultural histories according to the logic of different cities, blending media with urban life to continuously create new urban spatiotemporal interactions. Tang Yunbing (2020) summarized the development of urban public spaces as artistic objects, public domains, and communication mediums in fields such as communication and art studies, examining urban public spaces from a visual communication perspective where the visual representation system is continually practiced in public domains.

Moreover, some scholars have begun to focus on the impact of technology on the formation of the urban public space landscape in the context of societal spectacle. Li Jiayi (2013) proposed an interesting viewpoint in their research: “The development of consumer culture, entertainment culture, visual culture, and new media is propelling our society towards a spectacle society, where the cultural landscape of cities, as a hallmark of the times and urban culture, is being reconstructed along with social transformation.” This perspective underscores the close interplay between technology, culture, and social transformation.

However, current research on urban public spaces as communication content and the object of urban public spaces remains relatively limited. Yu Shuang et al. (2017) pointed out in their research that “urban images reflect the spatial reality of urban existence, constructing a mediatized imaginative space,” viewing images as carriers of urban content while emphasizing the importance of constructing a “communicative city” as a new path for interactive and dialogic interpersonal communication. While these studies offer insights into the relationship between urban public spaces and communication, further in-depth research and follow-up in this field are urgently needed.

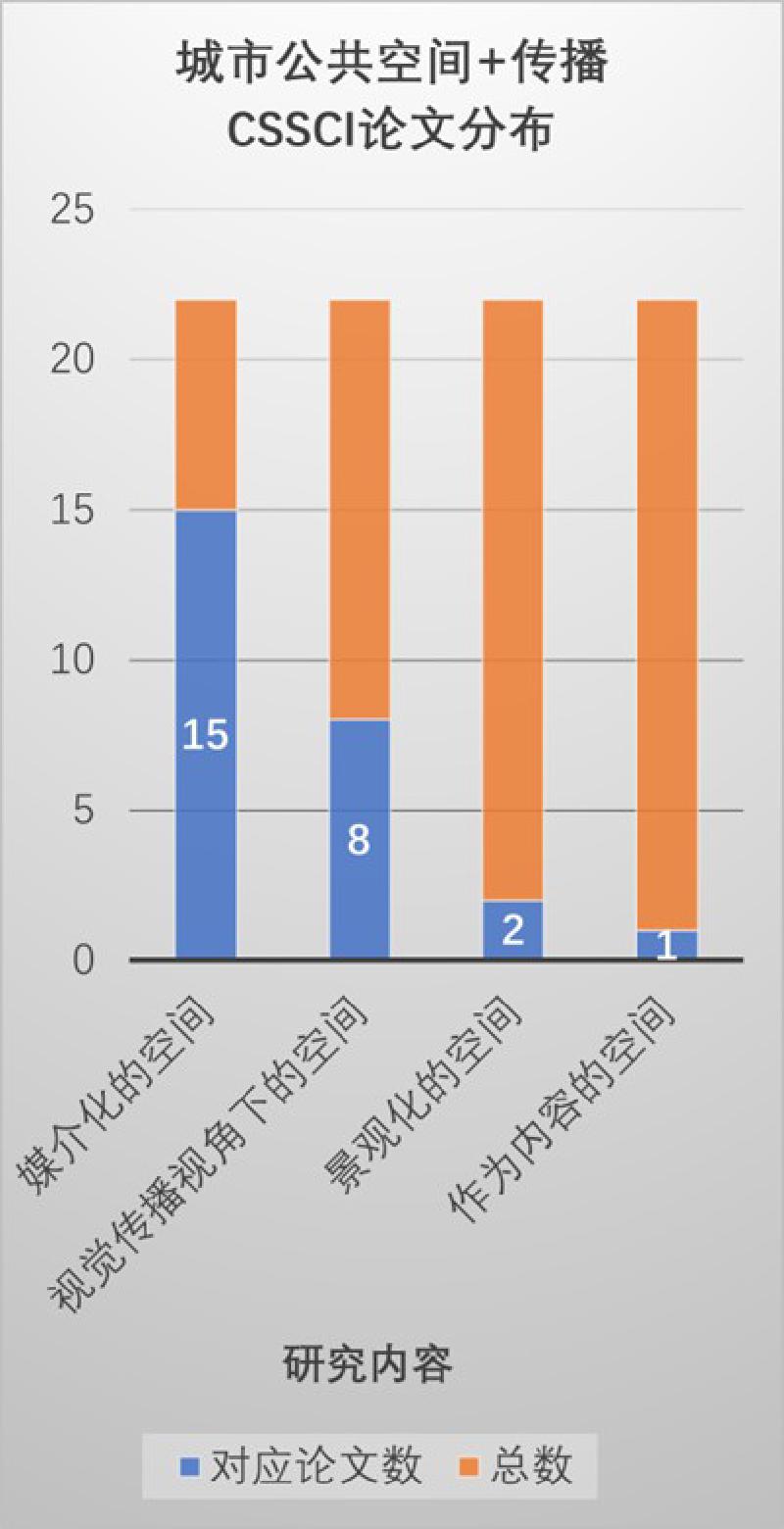

There are certain gaps in the overall research on communication in urban public spaces. This data chart highlights the relatively fewer directions of current research, indicating untapped potential and opportunities in this field. Future research can delve deeper into understanding the complex relationship between urban public spaces and communication, especially focusing on the objects of communication and their needs and attitudes towards urban public spaces, to advance the development of this field.

Urban Public Spaces and National Image

National image is the impression and evaluation formed in the international community and among domestic populations of a specific country based on its history, current situation, national behaviors, and activities.

Urbanization has been one of the themes accelerating China’s modernization process since the 21st century. However, Chinese urban images face the dilemma of being homogenized. At the same time, in the current new historical period, the rising China urgently needs to shape and communicate a national image as a major power. The linkage between urban image and public spaces has become a research focus for some scholars. Zheng Chenyu (2016) proposed that on the basis of the musical and internet carrying capacities of national image that he introduced, “urban image is an important carrier of national image carrying capacity, and virtual shaping of urban image is a crucial and malleable part of national image carrying,” further presenting four paradigms of transition from urban image shaping to national image construction: “knowing the autumn from a single leaf” and “a hundred flowers in full bloom,” “self-improvement without pause” and “moral integrity and bearing.” Xiao Xiao (2020), based on the context of the new media era, emphasized that the new media era provides favorable conditions for the interaction between national and urban images, advocating for creating urban images that align with the national image and utilizing the power of new media to disseminate urban images to a broader audience. Tan Zhen (2021) believes that urban image and national image are interdependent and mutually influential, exploring four functional dimensions of urban image in national image construction, including concrete functions, emotional functions, experiential functions, and identity functions.

While specific research on the relationship between urban public spaces and national image has received less attention in the past, it has recently gained significance. Tang Yunbing (2020) analyzed the national image on urban public spaces from a visual communication perspective, suggesting that urban public spaces, through visual elements like sculptures, art, and advertisements, serve as crucial platforms for constructing national image. These elements not only showcase regional cultures but also, through mass media dissemination, shape the core values of the nation, displaying its prosperity, multiculturalism, and modern face. This construction of visual image is not only an expression of national identity but also a means of international communication and cultural output. Furthermore, from the stages of art, media to intelligent development, public spaces witness the modernization process of cities and nations through various forms of visual image construction, serving as potent tools to showcase national image and culture on the international stage.

Further exploration in this research field will help us better understand the role of cities in the construction of national image, providing more effective pathways to shape a positive national image. In the current new historical period, China’s rise makes this research particularly crucial, offering new models for the interactive relationship between global urban images and national images. Research focusing on the relationship between urban public spaces and national image is expected to provide a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of national image construction and dissemination, contributing new perspectives and directions to the diverse development and international communication of Chinese urban images.

In conclusion, past research on urban public spaces mainly focused on exploring the attributes of spaces themselves while relatively neglecting the study of the participants in these spaces—the “people.” This is evident in the insufficient research on urban public spaces as communication content and the objects of urban public spaces in the study of urban public spaces and communication. Particularly in the context of the relationship between urban public spaces and national image, research is still in its early stages and requires more attention to the aspect of communication objects. Therefore, our research will focus on the communication objects in urban public spaces, emphasizing their roles as participants and receivers of information in urban public spaces to deeply analyze the impact of urban public spaces on the construction of national image, providing new perspectives for a more comprehensive and effective construction of national image.

Research Methods

Desk research—literature analysis

Empirical research—combining qualitative and quantitative approaches

Theoretical Framework

Utilization and Fulfillment

The theory of utilization and fulfillment focuses on the goals and satisfaction individuals seek when choosing and using media. This theory emphasizes the audience’s agency in relation to media, highlighting their purposeful and conscious selection and utilization of media to attain specific psychological and social satisfaction. In urban settings, the design of public spaces directly shapes the scenes in which individuals choose and interact. By creating engaging environments, urban design guides audiences to seek leisure, social, and cultural experiences within spaces. Diversified urban public space designs cater to the needs of various demographics, fostering community cohesion and cultural diversity. Such designs present a livable, culturally rich urban image, thereby cultivating a positive national identity.

We will utilize this theory to explore how to create urban public spaces that better satisfy the audience.

Sites of Memory

The theory of sites of memory, conceptualized by the sociologist Pierre Nora in “Realms of Memory,” refers to places that evoke collective memory, carrying historical and cultural significance, becoming symbols of shared memories. Integrating the theory of sites of memory into the design of urban public spaces entails creating locations that serve as carriers of collective memory. Through urban public space planning, we can establish places with historical heritage and cultural significance, using unique design elements and cultural symbols to evoke historical memories and cultural emotions, transforming them into shared scenes of perception and reminiscence. These places are not merely physical spaces but also bridges connecting the past, present, and future. Such designs not only reinforce the historical roots of a national image at the urban level but also enhance national cohesion through shared memory experiences.

We employ this theory to analyze urban social spaces with historical and cultural significance and explore the sustainable development of urban public space design.

Spatial Sociology of “Utilization-Experience”

The spatial sociology of “utilization-experience” is a theoretical concept proposed by Chinese scholar Ying Li Cheng, deriving from the influences of Lefebvre’s production of space and Giddens’ structuration theory on spatial research paths. Its core concept focuses on individuals’ practical behaviors and perceptual experiences in space. This theoretical perspective shifts the focus from traditional spatial structures and forms to people’s actual usage and perception of space, emphasizing the practicality of space. Lefebvre emphasizes that space is a product of social practice, while “utilization-experience” theory highlights individuals’ actual usage and perception of space. Giddens’ structuration theory focuses on the impact of social structures on individual behavior, whereas the “utilization-experience” theory emphasizes individuals’ subjective practices and experiences in space, introducing more subjective dimensions. Thus, the spatial sociology of “utilization-experience” encompasses three aspects of practical analysis: 1) individuals’ perception, utilization, and interaction with space; 2) interest groups engaging in space governance based on their feelings and emotional investments in space; 3) individuals’ communication activities in networked spaces and other usage behaviors.

We do not overlook the theoretical path formed by spatial practices and structuration theory, and we apply it to analyze the current state of urban public spaces. Additionally, we will employ the “utilization-experience” theory to analyze individuals’ practices and experiences in urban public spaces, considering how urban public space design can encourage people to enjoy public spaces, participate in community building, and contribute to image cultivation.

Case Study—Current State of Urban Public Spaces in China: A Case Study of Beijing

As the capital of China, Beijing bears the functions of being the national political center, cultural center, international exchange center, and technological innovation center. Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, following the grand blueprint outlined by General Secretary Xi Jinping to “adhere to and strengthen the core functions of the capital as the national political center, cultural center, international exchange center, and technological innovation center, thoroughly implement the strategies of creating a humanistic Beijing, a technological Beijing, and a green Beijing, and strive to build Beijing into an internationally first-class harmonious and livable capital,” Beijing has been undergoing profound transformation amidst the “additions and subtractions,” driving innovation leadership, endeavoring to effectively carry out tasks that benefit the people, and continuously enhancing the public’s sense of achievement, happiness, and security. On one hand, the unique nature of the capital gives it institutional and infrastructural advantages in international communication and external exchanges, carrying the responsibility of shaping the national image in the new era and enhancing China’s international influence; on the other hand, it bears the responsibility of improving the living environment of the people and building a livable city.

Therefore, focusing on Beijing as the subject of study, this group combines theoretical analysis with empirical research to primarily investigate the following three questions:

(1) What kind of urban public spaces does the country hope to build? (2) What kind of urban public spaces do the people wish to have? (3) The current status, strengths, weaknesses, and improvement measures of urban public spaces in relation to the dissemination of national image.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, sociologists began to consider space as a distinct research object, asserting that there is no pure natural space in human society; all spaces are social in nature, giving rise to the theory of spatial sociology. Zong Haiyong (2018) examined various research paths in spatial sociology, highlighting the practical, social, human-centric, and historical aspects of space as crucial attributes for understanding space. Wu Xinyin (2023), in exploring the overall image construction and communication paths of rural public cultural spaces, categorized the development of public spaces into three types: protection, new construction, and renovation.

This analysis section aims to examine problem (1) from a macro perspective.

Protection—The Case of Yuanmingyuan

Yuanmingyuan, a key cultural heritage protection site in Beijing with historical significance, follows the international consensus of “restoring old as old” and “minimal intervention” in cultural heritage preservation, as stated by Chai Xiaoming, the director of the Chinese Academy of Cultural Heritage. “Restoring old as old” refers to maximizing the restoration of cultural heritage to its original state after repair, allowing it to authentically showcase its historical appearance. Cultural heritage preservation exemplified by Yuanmingyuan adheres to the principles of “restoring as old” and “minimal intervention,” emphasizing authentic preservation (including material, cultural, spiritual, and functional aspects) as seen in the partitioned display of Yuanmingyuan relics based on authenticity (Zhang Chengyu, Viewing the Functional Zoning Display of Yuanmingyuan Relics from the Perspective of Authenticity, 2010).

In her book “Memory’s Place,” Nora defines memory’s place as sites that evoke collective memory, bear historical and cultural significance, and become symbols of shared memories. Built during the Qing Dynasty, Yuanmingyuan has a history of over three hundred years, making it a significant memory’s place for the Chinese nation with a certain temporal and spatial significance. Despite being ravaged by invaders at the end of the Qing Dynasty and losing its original appearance, the protection of Yuanmingyuan relics demands the retention of signs of invasion even when technology could restore its original appearance. This is because it transforms Yuanmingyuan into not just a symbol of Chinese garden art but also a tangible symbol of the historical fact of Chinese national suffering under invasion, serving as an educational memory’s place with historical significance.

As a medium for transmitting the traumatic memories of eyewitnesses at that time, Yuanmingyuan relics have transformed these memories into a collective national trauma memory through the process of historical development, acquiring a communal quality of collective memory and insisting on completing the vertical transmission of memory across generations. Its temporal and spatial significance and collective memory endow it with the ability to be reconfigured as a reference framework for collective identity in today’s context. Therefore, Yuanmingyuan, as a cultural symbol of garden art itself and the national trauma memory it carries, has been integrated and elevated into a complete national symbol, becoming a symbol of national and cultural identity through the continuation of collective memory.

The ability of cultural memory to consolidate national identity lies in a group deriving from this knowledge storehouse a consciousness of our entirety and uniqueness, a definitive affirmation (who we are) or negation (who we are not). Collective memory serves as a crucial intermediary for constructing national identity and state identity. The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China emphasizes that national image internally concerns national identity, social cohesion, political order, and policy support. Therefore, public spaces of the protection type, as historical and cultural symbols, internally reinforce the identity of the Chinese nation, cultivate a sense of community consciousness and emotion, and complete the transmission route of “protected public spaces—collective memory—national identity—state identity—national image.” (Reflection: The research on the transmission from national identity to national image is lacking, and this transmission process currently remains at an abstract psychological theoretical level.)

Construction—Taking “The Box” as an Example

“The Box” is formally known as the “outward-facing youth power center of The Box.” According to the Beijing Daily, the chief curator stated: “The CURETAIL solution proposed by URF redefines the relationship between ‘people, goods, and space’ in a curatorial retail manner, defining a new commercial space. The space serves as a curated stage, where brands and products become part of the exhibition. Here, consumption is not merely transactional; retail is not just about selling goods. Transforming curation into a new force in retail, with characteristics of scenarization, gamification, curation, and self-media, provides consumers with a more immersive cultural consumption experience, allowing exhibitors to maximize the effects of flash changes, cross-border interactions, and storytelling.” “The Box” outward-facing is not a traditional shopping center but rather a showcase or stage.

In other words, since its inception, The Box has not only served commercial purposes but also carried the functions of cultural exchange and human communication. Zong Haiyong believes that the humanistic critique of space path “places people and their environment at the center, emphasizes the subjectivity of individuals in space, seeks to understand and discover the values and meanings influenced and limited by culture, consciousness, background, and other factors in places and daily life.”

Therefore, we need to focus on the dual impact brought about by the appearance of The Box:

Firstly, it provides a physical space for offline communication among young interest groups and serves as a stage for young people’s personal interests. The space itself offers a high degree of freedom, allowing participants to make certain changes, which are determined by individual free will. In a sense, this realization of human agency in space reflects the centrality of human beings. Thus, the human-centric nature of the space is exemplified in The Box.

However, when considering the space’s impact on individuals, we must consider both users and observers: for young people who use this space extensively, The Box’s essence lies in commercialism, where “culture” is forced to serve as a means to promote consumption, masking the invasion of capitalism. Consumerist values will significantly influence and even alter the participants’ thoughts. For those who do not directly use this space but are exposed to it, the culture formed by this youth interest group may further reinforce negative stereotypes of young people, leading to increased ideological conflicts and communication barriers between generations and individuals.

Transformation—Taking 798 Art District as an Example

Lefebvre emphasizes that the transition from one mode of production to another inevitably entails the emergence of a new space. The birth of the 798 Art District has a specific historical background, confirming a monumental shift in the mode of production in Beijing and even in Chinese society, making it a typical case of architectural transformation in Beijing.

In the 1950s, China realized the importance of building a modern industrial system, especially indigenous high-tech communication equipment factories, and with assistance from the Soviet Union, established the “State-Owned 718 Joint Factory” during the “First Five-Year Plan.” However, after 1985, due to factors such as resource depletion and environmental pollution, the global industrial development cycle entered a period of decline, and traditional industrial production faced transformation and elimination. The “birth pangs of the times” directly led to the 718 Joint Factory shifting from profit to loss, with a large number of workers being laid off and factory buildings lying idle. It was not until around 2002 that with the gradual leasing of the idle factory buildings to art groups, the area began its transition from “718 Joint Factory” to “798 Art District.”

Today, the 798 Art District has become an important urban public space in Beijing. However, considering the transition from “Joint Factory” to art district, and the balance between “free” and “paid,” we must be concerned whether 798 has become an arena for the struggle between two ideologies.

The Popularization of Elite Aesthetics

The process of transforming 798 from an abandoned factory to the largest and most influential contemporary art hub vividly illustrates that in the context of globalization and market conditions, grassroots forces are surpassing the early idealistic pursuit of “utopia.” They are integrating the pursuit of art with the current social and human living conditions, actively seeking their own discourse power. The concept and actions of its transformation, as well as the open and public nature in which 798 Art District is presented to the public, demonstrate great foresight and practicality.

In essence, before the emergence of art districts, art was predominantly monopolized by the elite upper class. The appearance of the 798 Art District has given contemporary art an educational function in public art, serving as a crucial bridge for the public to understand and engage with contemporary art. Contemporary art and its artists have transitioned from being “underground” to being in the public eye. Through the expansion of new functions in art districts and artists’ villages, contemporary art has finally begun to integrate into public life, signifying the integration of art into people’s daily living spaces.

The Encroachment of Consumerism on Social Spaces

However, the path to popularizing art in 798 is accompanied by the encroachment of consumerism and the establishment of a discourse hegemony system. On one hand, 798, as a symbol of “elegance” and “bourgeoisie,” has shaped a group of people’s definition and self-perception of “art.” Regular visits to 798 have become a form of identity, predominantly for white-collar workers and those with a bourgeois inclination. People come here not just to shop but also to experience a certain emotion and cultural identity. Thus, art, like “fashion” and “consumption,” has constructed a new social class where the ability to understand art and the level of art investment become significant determinants of individual social standing. On the other hand, 798 provides constantly evolving spaces for exhibitions, operas, ballets, and more. In many cases, the public is compelled to purchase the latest viewing rights and forsake what is deemed as outdated art forms. This depreciation of art forms is fertile ground for consumerism, where a “capitalist” form of transaction has taken root in 798.

Using 798 Art District as a reference point, what truly demands attention are broader societal issues: the problem of industrial structural reform. In 2013, China officially implemented the “National Plan for the Transformation and Adjustment of Old Industrial Bases,” which involved adjusting and reforming industrial bases formed during the “First Five-Year Plan,” “Second Five-Year Plan,” and the development of “Third Front” regions, based on the layout and construction of state-owned heavy industry backbone enterprises. The planning period spans from 2013 to 2022. To this day, the transformation of all old industrial bases nationwide must be completed, signifying the partial transformation of communities holding collective memories of the heavy industrial era into urban public spaces, serving various functions such as citizen services, emerging industries, and commercial blocks.

However, the transformation of the 798 Art District should serve as a warning signal for us. We need to contemplate whether industrial factory spaces born out of socialism can uphold their socialist essence in the present era. How can two ideologies achieve balance in the same space?

Characteristics of Planned Urban Public Spaces in China

\1. The application of digital technology has become a focal point.

In the era of big data, the rapid development of digital technology has brought new opportunities for the field of public spaces. Taking the preservation of the Old Summer Palace as an example, although the principle of authenticity in preservation requires that the restoration and protection of the Old Summer Palace cannot fully return to its pre-damaged state, relevant departments have utilized digital technology to complete the restoration of the Old Summer Palace. Visitors can experience the digital reconstruction of the Old Summer Palace through technologies such as 3D scanning and virtual reality.

\2. Trends in integrating urban social, ecological, and economic structures are evident in scenic gardens and old industrial sites.

Using Beihai Park as an example, the transformation of the once private garden into a public park has embodied the principles of ecological civilization, creating a city park that integrates ecological conservation, traditional culture, and garden art. In terms of integrating into society and citizens’ lives, Beihai Park offers ice activities. As for old industrial sites, adhering to the principle of renovation without wasting land resources while preserving the historical significance of the industrial sites, focusing on ecological conservation as the core, restoration precedes transformation.

\3. Planning guided by a human-centric ethos

Empirical Research

From the preceding analysis, we have gained a general understanding of the type of public spaces the country aims to construct. This empirical research primarily focuses on the following issues:

Issue (2): What kind of urban public spaces do people hope to have?

Issue (3): The current status, strengths, weaknesses, and improvement measures of urban public spaces in relation to national image dissemination.

In summary, the results of this empirical research successfully address Issue (3), presenting improvement suggestions from the perspective of the audience. It also reflects that for more public-oriented urban public spaces, people express higher satisfaction. However, in politically charged urban public spaces, especially those with a red theme, there exists a certain degree of deviation between people’s actual perceptions and the urban public spaces advocated by the state.

Quantitative Research - Questionnaire Survey

A total of 122 questionnaires regarding “Beijing university students’ attitudes towards public spaces” were collected, with 21 invalid surveys excluded, resulting in 101 valid responses. Based on the questionnaire results, we can derive the following conclusions:

(1) The main urban public spaces frequented by Beijing university students are commercial areas and city parks.

(2) Students primarily seek entertainment and relaxation experiences in urban public spaces.

Conclusion (2) can be seen as the purpose and demand behind Conclusion (1). Due to students’ inclination towards seeking entertainment experiences and emotional relaxation, they are more inclined to choose commercial areas and city parks when engaging with urban public spaces.

(3) Convenience, comfort, aesthetics, uniqueness, and affordability are the primary reasons for students to choose public spaces.

Urban public spaces, as a form of “implicit” communication content and medium, are essentially a process of media usage for students when engaging with them. Based on usage and satisfaction, students inevitably have their own purposes for selecting public spaces. By correlating Conclusion (1) and Conclusion (2) with the graphical information provided by the survey results, we can deduce that convenience, comfort, aesthetics, uniqueness, and affordability are the main reasons why students choose public spaces.

To explain this phenomenon, we can employ Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can be categorized as physiological needs, safety needs, social needs, esteem needs, cognitive needs, aesthetic needs, self-actualization needs, and transcendence needs. Maslow posits that lower-level needs exert greater power and potential. As one moves up the hierarchy, the power of needs diminishes accordingly. Before higher-level needs can be met, lower-level needs must be satisfied (not necessarily to 100%). Thus, when selecting public spaces, consideration is also given to lower-order needs, such as practical aspects related to travel and expenditure. In the context of groups, the rapid economic and social development in contemporary China has largely fulfilled physiological and safety needs at the societal level, prompting a desire for satisfaction of higher-order needs. Particularly among the younger demographic represented by university students, the expression and satisfaction of self-worth, social and aesthetic needs gradually become their primary objectives for “external” activities. Commercial districts and natural parks in urban spaces precisely cater to participants’ pursuit of individualized and aesthetic aspirations.

(1)University students exhibit a strong willingness to communicate in public spaces.

Whether through online group communication (the essential nature of the internet is the dissemination by a highly diverse collective of communicators, indicating the spontaneous gathering of a highly diverse network of communicators in cyberspace, engaging in communicative activities in a de-structured manner, transforming the originally non-standard social collective behavior into a standard form of communication in the internet realm, in other words, the evolution of dispersed societal behavior characteristic of the mass communication era into a normalized social aggregation within cyberspace) or interpersonal communication among friends, university students, overall, display a strong inclination for communication. However, their willingness to communicate in specific categories of urban public spaces varies slightly. When disseminating urban public spaces online, university students tend to prefer spaces that align with their own inclinations. Yet, in interpersonal communication, especially with individuals from different geographical locations, they are more inclined to choose public spaces that exhibit regional characteristics.

(2)University students show little interest in “red culture” urban spaces.

In terms of the willingness of university students to communicate in public spaces associated with “red culture” and patriotic education, which embody official ideological values, these spaces rank low in students’ communication preferences. Nearly 70% of individuals would not bring friends to “red culture” spaces, and less than 2% would visit patriotic education spaces and engage in communication about them on the internet.

Our analysis indicates two main reasons for this:

① Psychological Avoidance Mechanism

Public spaces related to “red culture” and patriotic education tend to categorize items based on so-called “scientific” or “objective” principles, creating a strong sense of order that evokes solemn and reverential psychological responses in layout and visual presentation, establishing a tense and serious atmosphere.

Furthermore, these urban public spaces in China often showcase historical memories that may include national traumas, such as revolutionary battles, the Korean War, and more recent events like the pandemic. Visiting such public spaces often entails a retrospective journey through history. During this historical reflection, visitors may experience feelings of melancholy, regret, and sadness. In more severe cases, individuals may suffer from vicarious psychological trauma. Vicarious psychological trauma refers to various psychological abnormalities indirectly caused by witnessing numerous brutal or destructive scenes that exceed the emotional and psychological tolerance limits of some individuals, leading to severe mental and emotional distress, even potential mental breakdowns (Liu Jun, Capital Medical University Affiliated Hospital).

Therefore, individuals may be influenced by a psychological avoidance mechanism (wherein individuals may choose to avoid thinking about, evade, or escape emotions such as stress, threats, or sadness to alleviate discomfort) and refrain from selecting such public spaces for visitation and communication.

② Self-Determination

Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan jointly developed the Self-Determination Theory, which asserts that environmental conditions that satisfy individuals’ basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness can enhance people’s initiative, creativity, and happiness.

Autonomy: Individuals need to feel that their actions are self-chosen rather than imposed by external sources—the reasons for their actions exist within themselves rather than in external controls. The strong disciplinary and ideological significance of public spaces related to “red culture” and patriotic education places the audience in a passive position, particularly for young adults, such as university students, who highly prioritize personalized self-value realization and strongly reject public spaces that do not allow for a sense of autonomy.

Competence: Individuals must feel capable enough to engage in certain behaviors to achieve desired outcomes. Associated with intrinsic motivation is the spontaneous pleasure and sense of accomplishment that arises when individuals engage freely in goal-oriented activities. In a context filled with academic pressures, existential dilemmas, life stresses, and competitive pressures, young adults, represented by university students, are unable to choose public spaces that induce stress and oppression during their free time. Instead, they seek to alleviate pressure through their participation in public spaces.

Relatedness: In experiencing competence and autonomy, individuals also need to feel connected to others. This need for relatedness, the desire to love and be loved, to care and be cared for, essentially a social need, can only be clearly felt through interpersonal interactions. Existing public spaces related to “red culture” and patriotic education offer a simple, cold, one-way flow of information, lacking the reciprocal participation of individuals and the exchange of information in a bidirectional manner.

Qualitative Research - In-depth Interviews

Considering the feasibility of operation and the representativeness of the sample, this group systematically selected three university students at the Communication University of China for in-depth interviews. To safeguard the privacy of the interviewees, pseudonyms were used for all individuals interviewed.

Following the extensive interviews, the general information of the interviewees can be summarized as follows:

| Name | Wang Chenxi | Li Siyuan | Zhang Mu |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hometown/Current Residence | Qingdao/Beijing | Beijing/Beijing | Beijing/Beijing |

| Education | Undergraduate | Undergraduate | Undergraduate |

| Preferred Public Spaces | Commercial districts, art districts, unique neighborhoods | Landmarks, sports venues, museums | Parks, squares, landmarks |

| Communication Willingness | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Information Channels | Xiaohongshu | Xiaohongshu | Xiaohongshu |

This group will analyze the results of this in-depth interview from the following three aspects.

Audience Engagement

What kind of public spaces do the public prefer? What experiences do they hope to encounter in public spaces? The outcomes of this question to a certain extent reflect the differences in cognition and perception between the “state” and the “people” in public spaces, providing insights for attracting user engagement in public spaces. The findings of this in-depth investigation reveal that the public’s expectations for the content of public spaces are closely related to the categories of the spaces themselves. While public spaces exhibit common features in terms of infrastructure and architectural planning, the arrangement of activities and cultural characteristics are strongly influenced by individual interests, demonstrating a significant degree of heterogeneity.

Based on the results of the in-depth investigation and questionnaire categorization, this group will elaborate on the results according to the categories of public spaces.

(1) Commercial Districts and Art Zones

During the in-depth interviews, we observed that when commercial districts take on the nature of urban public spaces, respondents often overlook their commercial features, reduce their purchasing behavior, and instead focus on the humanistic characteristics. In other words, respondents believe that commercial districts possess a cultural blend, where interactions and communications between tourists from different regions and locals allow them to experience the local customs and culture. Simultaneously, the presence of commercial districts can to some extent meet the social needs of respondents, with “being accompanied by friends” becoming a common practice in commercial districts.

Wang Chenxi: “Places like Nanluoguxiang, Drum Tower, and Shichahai are particularly enjoyable to stroll through. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly why they are so pleasant to visit, but when you walk through places like Citywalk, it can be quite intriguing, even if you don’t buy anything… It’s lively and bustling, so you just go there and walk around. Each time, you follow the same route, starting from Nanluoguxiang, weaving your way to Drum Tower East Street, then circling around, eventually reaching Shichahai. That’s usually where you end up, and if you feel like it, you can take the subway to enjoy the view or go shopping.”

Zhang Mu: “Places like Nanluoguxiang are basically tourist attractions. I feel like it’s part of a cluster of attractions, so many people say that when out-of-town visitors come, they usually visit… I go there sometimes too, usually with friends, and then we casually stroll through Beihai Park.”

The high influx of visitors brings about a dual effect for commercial streets: on one hand, commercial streets have the potential to promote consumption while also serving as a platform for cultural exchange; on the other hand, authorities need to emphasize the character and cultural aspects of commercial districts to showcase regional uniqueness.

Regarding art zones and art centers, respondents exhibited similar characteristics: they value the event content and economic expenditures. In terms of events, exhibitions that are novel, interesting, rare, and enriching in knowledge are more welcomed by respondents. Economically, respondents are willing to spend around 100-200 yuan on art exhibitions per visit.

Due to the lack of professional aesthetic appreciation among most audiences, individual interests play a significant role in the selection of art categories, making it challenging to draw universal conclusions.

(2) Landmarks and Iconic Buildings

Landmarks and iconic buildings are public spaces commonly chosen by out-of-town and foreign tourists when exploring a city. Unlike commercial districts and art centers, landmarks and iconic buildings inherently possess stronger political significance, representing a microcosm of urban culture and characteristics. However, tourists tend to steer clear of political topics during their travels, making the cultural features and construction conditions of landmarks and iconic buildings their primary concerns.

In terms of infrastructure, respondents indicated that they are not particularly concerned about the construction of amenities like Wi-Fi, rest areas, or restrooms, considering them as “tolerable,” and instead place greater emphasis on the construction and maintenance of the landmarks themselves.

Li Siyuan: “I believe that if historical buildings have been damaged due to historical factors, such as invasions or the Cultural Revolution, and are unable to undergo proper restoration, like in the case of the Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan), where there are ruins, it still carries a beauty and allows you to sense a historical heritage in a way. However, I cannot accept it being used as a dumping ground or left partially restored, where you can clearly see traces of inconsistent repair work. I find it quite absurd, and I am even more unable to accept it being dirty and disorderly. Either plan properly or present it in its post-damaged state; don’t keep patching it up.”

Overall, respondents hope that cultural landmarks can ensure beauty and cleanliness, or restrict access to areas that have undergone unified planning, have well-established tourist routes, and have adequate facilities, to ensure a comfortable and immersive experience for visitors.

For natural attractions, respondents noted that the main issue is the vast area of the scenic spots, making it challenging for individuals to explore everything in one go and demanding high physical endurance from visitors. Respondents expressed a desire for the promotion and availability of sightseeing vehicles in scenic areas to provide full-service assistance to visitors.

Regarding cultural features, respondents believe that enhancing the regional characteristics of landmarks and iconic buildings, leveraging local culture to highlight the advantages of the scenic spots, and creating urban public spaces with uniqueness, historical significance, and memorability are essential to avoid architectural homogeneity.

Zhang Mu: “I think one thing that’s particularly unfavorable nowadays is when a city builds something like a clock tower or a sculpture, and then when you travel to another city, you see something similar, it becomes quite uninspiring. Each city’s architecture is unique and has its own distinctiveness; if every place has the same kind of structures, then it becomes unnecessary.”

In the perception of the public, the inclusiveness of urban public spaces such as squares, parks, and green areas has been further strengthened. These urban public spaces have completely shed political and cultural influences to become purely areas for public leisure activities.

In-depth interviews have revealed a familiarity and indifference towards squares, parks, and green areas among the interviewees. When asked about their views on small public spaces near their residences, interviewee Wang Chenxi expressed that small parks are “not very important” and their absence would not have an impact. Interviewee Li Siyuan described them as “generally planned,” while interviewee Zhang Mu mentioned they do not frequent such spaces much, usually only seeing elderly people dancing in the square.

This outcome to some extent indicates a noticeable generational difference in the use of urban public spaces. Squares, parks, and green areas belonging to residential areas have specific participant groups, primarily the elderly residents of nearby neighborhoods. Younger generations, on the other hand, show less concern for proximity and are willing to visit city public spaces further away for activities.

During the in-depth interviews, interviewee Li Siyuan expressed a love for museums and non-profit exhibitions. Li Siyuan believes that exhibitions with a sense of history and the ability to reflect changes in specific historical periods and regions are more likely to pique visitors’ interest. Li Siyuan also outlined several key features for constructing a museum that appeals to the audience:

“Firstly, it should have permanent exhibitions reflecting the history of the city and the cultural development of a specific area. There should be several galleries that are always open, as well as rotating exhibitions showcasing different themes to keep visitors engaged. A museum must have spaces prepared for receiving and displaying these rotating exhibitions.

Furthermore, in terms of lighting and spatial layout, it should be rational. The Chinese History Museum has a major issue where despite looking large from the outside, due to the design of stairs and elevators inside, the actual exhibition space is quite small, creating a discrepancy. Additionally, in terms of historical and cultural content, the supplementary educational material should be written diligently and logically, without errors. It should not be limited to just a word or two, casually placed next to an object, but should provide detailed information on the time period, origins, and significance.”

The results of this in-depth interview indicate that China still has a long way to go in the construction and promotion of red public spaces. Most interviewees expressed a negative willingness to participate in red public spaces, stating they “do not want to go” and “are not interested.” When asked for specific reasons, interviewees mentioned:

“If it’s purely for ideological propaganda, to be a bit politically incorrect, I have no interest. But if it’s accompanied by items used by martyrs during the war, even if it’s just glasses, guns, or shoes, then I would be interested.”

To achieve better dissemination, red spaces and patriotic education need to consider the audience’s receptiveness. By demystifying theoretical knowledge and ideological propaganda and conveying them in an easily understandable manner, a more effective communication can be achieved. Interviewees hope that red public spaces go beyond long-term ideological propaganda and increase the frequency of material exhibitions. By showcasing objects from the wartime era that carry national memories, citizens can further embrace patriotic education.

Audience Communication

Contemporary young people demonstrate a strong dependence on the internet for obtaining information related to public spaces. The three interviewees in this in-depth study all expressed that they use the Xiaohongshu platform to search for relevant posts when planning their travels, drawing on others’ experiences and planning their own travel routes based on these posts. Interviewee Wang Chenxi also mentioned that “occasionally coming across travel posts” enhances their desire to travel. It is evident that the internet has become an important medium for public space communication, and self-media recommendations have become a highly influential mode of communication. Therefore, in the process of portraying a country’s image using urban public spaces as the object, it is crucial to pay full attention to the power of internet self-media, make good use of the benefits of internet celebrities, and create a multifaceted new image of China in the modern era to counteract the stigmatization and demonization of China.

This in-depth interview also focused on the audience’s communication intentions, exploring the willingness of citizens to spread relevant content on the internet and the factors influencing this after engaging in urban public spaces. The research results are as follows:

(1) Media Selection Dominated by “Acquaintance Socialization”

When asked whether they would engage in behaviors such as writing or posting about their experiences in urban public spaces, the three interviewees showed a common preference for using platforms with “acquaintance socialization” characteristics, with friends’ circles being the primary platform for posting content, while social media such as Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin were not their preferred choices.

The reasons given by the interviewees included “infrequent use” and “lack of a posting habit.” It is worth noting that the interviewees mentioned that they did not have concerns about privacy breaches but rather that they do not frequently share content on social media platforms and are not accustomed to this form of life sharing.

While it may be coincidental that the three interviewees are all inactive users of social media platforms, we still need to consider the possibility of low willingness among young people to post content related to urban public spaces and reflect on the strengths and weaknesses in international communication. Recommendations on this point will be detailed in the following sections.

(2) Content-Led Space Selection

Especially for non-tourist spots or landmark buildings in urban public spaces, the software facilities (such as activities) and hardware facilities (such as architectural aesthetics) of the space become the main factors influencing the audience’s communication willingness. Regarding activities, the interviewees expressed a desire for authorities to hold regular events in urban public spaces, as this would greatly stimulate participants’ interest and enhance their willingness to communicate.

In general, activities with the following characteristics are more likely to enhance the audience’s communication willingness:

- Aesthetic appeal: Activities should embody visual and auditory aesthetics and artistic features.

- Novelty: They should broaden the audience’s knowledge and satisfy their curiosity.

- Entertainment: Audiences should be able to entertain themselves fully, and the effects of internet celebrities and celebrities can further stimulate audience participation and communication.

- Economic viability: Audiences seek activities that offer value for money.

Wang Chenxi: “Because recently, Anaya had a Christmas event, and it seemed to have a lighting ceremony. When I saw it, I really wanted to go, but it was quite expensive. The hotel was already expensive, and it became even more expensive at Christmas, so I didn’t go.”

Li Siyuan: “I always feel that things with strong color contrasts or eye-catching shapes make me visually enjoy them more, and I can take really nice photos to post on my friends’ circle.”

Zhang Mu: “I mainly look at exhibitions or visit museums and then post on my friends’ circle. On one hand, it’s visually appealing, and on the other hand, I want to show off by posting these high-end things, making me appear elegant and sophisticated.”

(3) Prominence-Led Space Selection

“Prominence-led space selection” specifically refers to spaces such as tourist attractions and landmark buildings that are more favored by visitors. A rough search of urban public space images on the internet shows that there are more pictures of well-known scenic spots like the Temple of Heaven and the Forbidden City, aligning with tourists’ psychological tendencies.

Tourist spots, scenic areas, and landmarks embody the cultural characteristics and historical heritage of regions, cities, and even countries, making them important subjects for political and cultural communication. Strengthening the emphasis on these public spaces is crucial for the external communication of a country’s image. Further details on this will be elaborated in the subsequent sections.

Development Recommendations

In the course of this in-depth interview, the interviewees made two suggestions regarding the development and planning of public spaces in Beijing:

(1) Technological Empowerment

The interviewee, Wang Chenxi, mentioned the empowerment of urban public spaces with digital technology, especially for spaces such as scenic spots and historical buildings that are difficult to modify.

Wang Chenxi: “Beijing has many ancient towers and buildings, like the Drum Tower. When you visit these places, you may just glance at them as historical relics without fully appreciating their historical value. Similar situations occur with the ancient city towers in Xi’an. If activities, such as murder mystery events, were held inside these buildings, utilizing their historical context to engage visitors, it would add more meaning. However, if these spaces remain inaccessible, they are merely preserved but not fully utilized.”

The current prevalent digital technology used for urban public spaces is digital exhibition halls, but they offer limited physical engagement for users and fail to effectively convey the intrinsic value of public spaces to the audience. There is a need to enhance the practical application of emerging technologies in digitizing historical buildings, using digital entertainment as a means to increase public participation and dissemination of urban public spaces.

(2) Unified Style

Specifically concerning the urban planning of Beijing, the interviewees believe there is a need to balance history and modernity, construction and preservation, to achieve stylistic consistency in architecture. The disharmony in Beijing’s public spaces arises from the juxtaposition of classical and modern architecture, hindering the formation of a unified cultural domain within the space. Strengthening this aspect could potentially enhance the public’s willingness to engage and communicate further.

Li Siyuan: “Near the Olympic Forest Park, where I previously visited the Chinese Academy of History, some highly modernized buildings appeared. These structures, possibly constructed during the building of the Olympic Park to align with its theme, featured a mix of metallic modernity that slightly stood out. Alongside these were government buildings with a very serious classical style and museums attempting to portray the traditional red walls and green tiles style. This clash of historical styles in close proximity… I understand Beijing’s challenges with its large population and diverse urban services, leading to the construction of numerous buildings. However, this process often results in conflicting initial plans being continually superseded by new ones, resulting in a somewhat orderly but personally disagreeable urban landscape.”

Summary, Analysis, and Design

Hardware Planning

(1) Creating a People-Oriented and Livable Urban Environment

Regarding internal dissemination, the current focus remains on creating a livable and harmonious city, in line with current policy directions and basic requirements. However, at the operational level, it is essential to solicit opinions from various sources and consider the actual needs of the people in their daily lives. In this regard, the empirical research conducted by our group may play a significant role.

(2) Grounded in Local Culture, Constructing Unique Spaces

This recommendation stems from empirical research results. The materiality of urban public spaces can influence their communicative effects to some extent. Therefore, spaces should embody cultural characteristics that can be symbolized or easily symbolized, showcasing regional and national features. Locally grounded spaces with cultural distinctiveness can enhance users’ national pride and cohesion, strengthen civic cultural identity, and boost cultural confidence. In international communication, such spaces can help foreign individuals and social groups gain a multifaceted understanding of China, counteracting existing stereotypes and improving China’s international image.

(3) Embracing Individuality by Moving Away from Over-Design

Often, human spatial behaviors, lifestyles, and identity cannot be “designed” but rather observed, respected, accommodated, and guided. Officially designated public spaces, despite meticulous design, can become overly managed or commercialized, leading to spaces imbued with a sense of regulation that may pressure participants.

Communication Methods

(1) Constructing a Multidimensional Outbound Communication Matrix

As mentioned earlier, the likelihood of the youth group in posting content related to urban public spaces being low needs to be considered. However, for urban public spaces to reach the masses, they must undergo a process of symbolization, based on internet platforms and social media as mediators. Simultaneously, in accessing information about China, foreign populations have far fewer channels compared to domestic audiences, making social media a critical element. Hence, the willingness of the audience to communicate internationally is more critical than domestically, requiring a higher level of professionalism from communicators. Thus, our group believes that the focus of international communication should not be on encouraging ordinary people to participate and increase their willingness to communicate but on organizing official elites, professional communicators, and grassroots organizations to construct an outbound communication matrix through official media, official social media accounts, self-media, and other diverse forces, forming a communication method more suitable for the internet era.

(2) Balancing Seriousness and Entertainment in Parallel

Currently, China’s external communication heavily relies on official media and accounts for content dissemination. While this approach allows professionals to determine the content of communication, ensuring a positive, proactive, and authentic image of China, it may lead to resistance from foreign populations already holding stereotypical impressions of China. Official symbols’ appearance could potentially trigger resistance, hampering effective content delivery and perpetuating stereotyped perceptions of China. Therefore, our group believes that prioritizing entertainment methods is essential, combining seriousness with entertainment to enhance external outputs. In past global ideological struggles, some nations have proven the effectiveness of entertainment in shaping ideologies, using entertainment products like films, books, and music to convey their national values. Today, the majority of ordinary people still lack the resilience to resist entertainment shaping ideologies. Therefore, our group emphasizes the power of entertainment in China’s cultural externalization, advocating for a change in the current paradigm through localized adaptations of the above methods to suit the national context, thereby subtly influencing international thoughts and perceptions.

Reference

[[1]] 刘思达.社会空间:从齐美尔到戈夫曼[J].社会学研究,2023,38(04):142-159+229.

[[2]] 陈竹,叶珉.什么是真正的公共空间?——西方城市公共空间理论与空间公共性的判定[J].国际城市规划,2009,24(03):44-49+53.

[[3]] 营立成.迈向什么样的空间社会学——空间作为社会学对象的四种路径与反思[J].中国社会科学评价,2019,(01):50-63+142-143.

[[4]] 刘儒,陈舒霄,王迪.城市居民感知的公共空间正义测度与优化[J].统计与信息论坛,2022,37(10):89-102.

[[5]] 桑劲,潘珂,孔诗雨.城市公共空间“自下而上”供给机制研究[J].城市发展研究,2023,30(07):79-87.

[[6]] 孙振华.公共艺术的观念[J].艺术评论,2009(07):48-53+47.

[[7]] 杨文会.论现代城市中的公共空间艺术[J].河北大学学报(哲学社会科学版),2004,(04):56-58.

[[8]] 周成璐.社会学视角下的公共艺术[J].上海大学学报(社会科学版),2005,(04):92-98.

[[9]] 邹锋.公共艺术的社会性[J].文艺研究,2005,(08):143-144.

[[10]] 孙振华.公共艺术的观念[J].艺术评论,2009(07):48-53+47.

[[11]] 赵君香.视觉传播语境中城市博物馆的公共空间设计——以洛杉矶盖提博物馆为例[J].装饰,2015,(03):128-129.

[[12]] 林元城,章佳茵,李路华等.城市情感地理与空间治理:广州市区宣传类户外广告案例[J].世界地理研究,2021,30(05):1083-1095.

[[13]] 苏状.公共屏幕传播与公共空间重构[J].南京社会科学,2012,(09):88-94+109.

[[14]] 陈霖.城市认同叙事的展演空间——以苏州博物馆新馆为例[J].新闻与传播研究,2016,23(08):49-66+127.

[[15]] 严亚,董小玉.城市空间“场景”中的青年媒介想象[J].南京社会科学,2017(04):113-117+132.

[[16]] 潘霁.地理媒介,生活实验艺术与市民对城市的权利——评《地理媒介:网络化城市与公共空间的未来》[J].新闻记者,2017,(11):76-81.

[[17]] 汤筠冰.论城市公共空间视觉传播的表征与重构[J].现代传播(中国传媒大学学报),2020,42(10):25-30.

[[18]] 李佳一.论景观社会的城市文化新景观[J].艺术百家,2013,29(S2):62-68.

[[19]] 于爽,王玉玮.影像的城市空间与现代性呈现——第五届中国影视青年论坛综述[J].现代传播(中国传媒大学学报),2017,39(05):158.

[[1]] 来源:光明日报报道《新中国70年国家形象的建构》

[[2]] 郑晨予.城市形象虚拟塑造的中国化与全球化——兼论与国家形象承载力的转换视角[J].社会科学家,2016(02):29-33.

[[3]] 潇潇.新媒体时代的国家形象与城市形象互动[J].新闻传播,2020(02):108-109.

[[4]] 谭震.城市形象与国家形象建构的关系及功能研究——基于近三年对外传播优秀城市案例的分析[J].国际传播,2021(03):78-85.

[[5]] 宗海勇.空间社会学视阈下城乡空间关系演进研究[J].南通大学学报(社会科学版),2018,34(06):109-115.

[[6]] 来源:新华社报道《北京:向着国际一流的和谐宜居之都迈进》

[[7]] 叶涯剑.空间社会学的方法论和基本概念解析[J].贵州社会科学,2006(01):68-70.

[[8]] 宗海勇.空间社会学视阈下城乡空间关系演进研究[J].南通大学学报(社会科学版),2018,34(06):109-115.

[[9]] 吴欣彦.乡村振兴背景下乡村公共文化空间整体形象建构与传播路径[J].新闻爱好者,2023,(02):76-78.DOI:10.16017/j.cnki.xwahz.2023.02.024

[[10]] 路璐,吴昊.多重张力中大运河文化遗产与国家形象话语建构研究[J].浙江社会科学,2021(02):133-139+132+159-160.

[[11]] 李琳,林子苏.从“718联合厂”到“798艺术区”:时代契机与文化重构的双重历史表征[J].美术研究,2022(05):120-124.DOI:10.13318/j.cnki.msyj.2022.05.016.

[[12]] 方李莉.城市艺术区的人类学研究——798艺术区探讨所带来的思考[28][J].民族艺术,2016(02):20-27+47.DOI:10.16564/j.cnki.1003-2568.2016.02.003.

[[13]] https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2013/content_2441018.htm

[[14]] 隋岩,群聚传播——互联网的本质[J].现代传播,2023.